A

Angela Kezengwa

Guest

doctype html>

From the outside, 12-year-old Jefferson and his 11-year-old brother Brian (not their real names) look like any other pair of rural Kenyan kids; competitive, playful, brimming with energy.

But beneath their joy lies a carefully measured routine: insulin shots, blood sugar checks, strict meal schedules, and constant vigilance. Because both brothers live with Type 1 diabetes.

Brian, the secondborn, was just four years old when he was diagnosed. His mother, Rose (a pseudonym), had already seen the signs before. Because two years earlier, she had walked the same terrifying path with Jefferson, the eldest. “My parents had encountered it before,” Brian says matter-of-factly. “Through my elder brother, Jefferson. He was diagnosed when he was just two.”

Now in their pre-teen years, both boys have grown up knowing the language of illness. They understand carbs, ketones and how easy it is for one wrong snack to throw their whole body out of balance.

“How Much Sugar Is In This?”

That’s the question that echoes through their household every time a packaged snack enters their orbit, from a roadside mandazi to a brightly-colored packet of biscuits. And it’s not always easy to get an answer.

“Sometimes it says ‘natural flavor’ or ‘no added sugar’, but when I check their blood sugar after, it’s high,” says their mother, Rose, holding up a crumpled snack wrapper. “What do those words even mean? Why can’t it just be clear?”

In her hands is what looks like an ordinary packet,but for her family, it could mean a dangerous sugar spike, a sleepless night, or even a trip to the hospital.

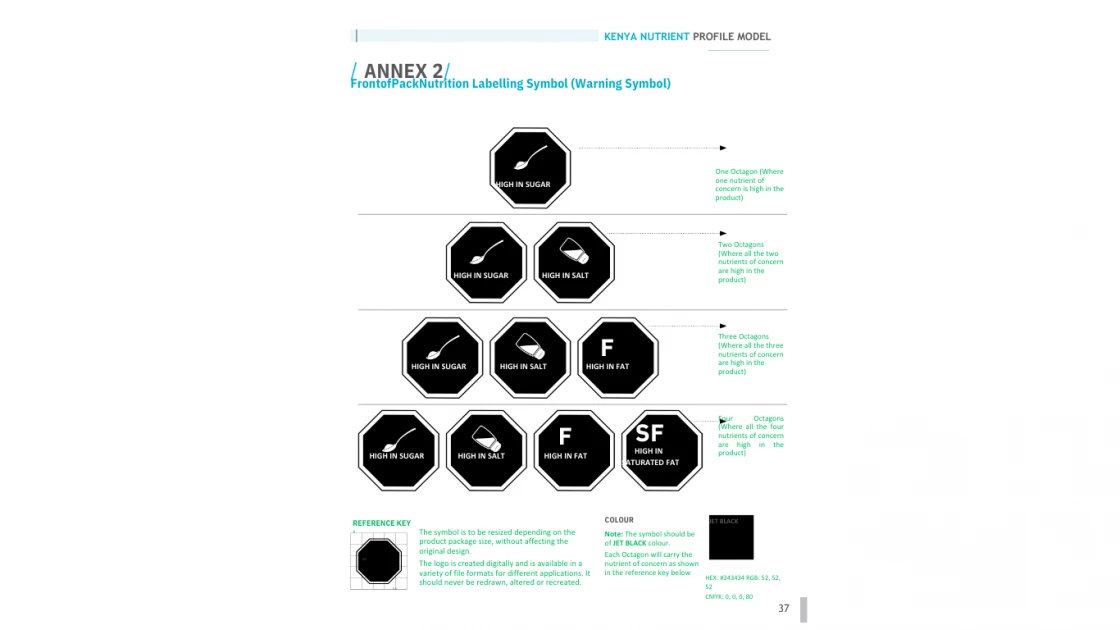

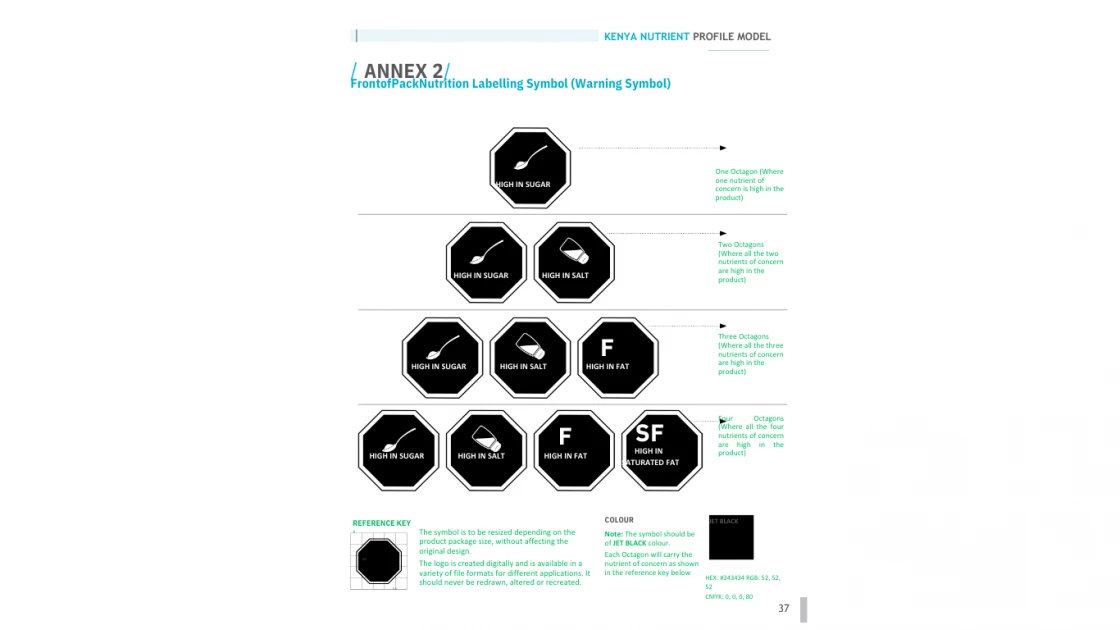

This is why Front-of-Pack Labelling (FOPL) could be a game-changer. FOPL involves placing clear, visible warnings, such as traffic light symbols or black stop signs, on the front of food packages to indicate if a product is high in sugar, salt, or unhealthy fats.

Unlike the confusing jargon of ingredient lists, FOPL speaks plainly. And for families like Rose’s, plain is powerful.

In countries like Chile and Mexico, FOPL has already changed lives. For Chile, according to the Global Food Research Program, Chile’s food labeling law, implemented in phases from 2016 to 2019, requires front-of-package black octagonal warning labels on products high in calories, sugar, saturated fat, or sodium.

These "high in" products cannot carry health claims related to the excess nutrient and face strict marketing restrictions, including bans on child-targeted advertising and limitations on TV ads from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. Additionally, such products cannot be sold or promoted in schools or nurseries.

Mexico has also introduced strict food labeling regulations to promote healthier consumer choices. Under the revised Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-051, implemented in October 2020, packaged foods high in sugars, fats, calories, or sodium must carry black octagonal front-of-pack (FOP) warning labels like “Exceso Azúcares” meaning excess sugars or “Exceso Sodio” meaning “Excess sodium.”

The rollout follows a phased approach: the first phase introduced the warning labels, while the upcoming second phase tightens rules on marketing, restricting the use of characters, endorsements, and health claims on products with warning seals. The aim is to improve transparency and protect public health, especially among children.

But in Kenya, the policy is still in limbo, tangled in red tape, industry resistance, and legislative delay. “We are advocating for the urgent implementation of a front-of-pack warning label system by 2026,” says Anne Swakei, NCD Alliance Kenya, a consortium pushing for action on food environment policies in Kenya. “It’s not just about consumer rights, it’s a public health imperative.”

A Biscuit, a Spike, a Lesson

“One time I ate a biscuit from a shop,” Jefferson recalls. “It looked healthy, brown color, said something about oats. But later, I felt dizzy. I checked my sugar, it was too high.” He shrugs, but the lesson lingers. Not all food that looks healthy is healthy. And not all food that claims to be “natural” is safe for them.

These aren’t lessons a child should have to learn the hard way. But in the absence of effective policy, the burden of education, monitoring, and prevention has fallen almost entirely on Rose’s shoulders.

“We want to help families distinguish between safe and unsafe products instantly,” explains Swakei. “A nutrient profile model (NPM) would classify foods based on saturated fat, sugar, and sodium content and FOPL would bring that information directly to consumers.”

Rose never imagined she’d become an expert in pediatric diabetes. She had never heard of Type 1 until Jefferson collapsed one Sunday morning while getting ready for church.

“I went to dress him. When I lifted him out of bed, he was limp. His mouth was full of thick saliva, and his breath smelled awful. I called his father. He rushed him to hospital.”

She pauses, “I honestly thought they’d be back in time for church.” Instead, she was thrown into a world of IV drips, insulin regimens, blood sugar monitors, and endless questions. “I asked, ‘Diabetes? In a child?’ I thought only old people got it.”

Back home, the questions were crueler. Was it witchcraft? A punishment from God? Why inject a baby? “Some said, ‘Don’t inject him, just pray and it will go.’ Others blamed me. I cried so much. I was green. I didn’t even know how to inject him without hurting him.”

Two years later, Brian fell ill—and Rose’s worst fear returned. Another diagnosis. Another child. Another lifelong journey. “I had become a full-time caregiver, whether I liked it or not.”

A Quiet Father, a Heavy Load

Rose isn’t entirely alone. The boys’ father, once married to another woman, now living apart, does provide financially. He pays school fees, covers some medical costs. But emotionally, and physically, he’s absent. “He’s not really there with us,” Rose admits. “He helps, yes, but the day-to-day, the hospital visits, the insulin checks, that’s all me.”

Rose says that he went back to his first wife, leaving her with the boys. She worries sometimes about what the emotional distance means for her sons. They rarely speak about their father, but she sees it in the quiet moments, when they sit too long by themselves, or when they ask questions she doesn’t always have answers for. “I know they feel the gap. But I also know I have to be strong. For both of them.”

Labels That Could Save a Life

For Rose, every school term is a dance of logistics. Ensuring teachers know the boys’ symptoms. Checking in with the school nurse. Packing snacks. Monitoring moods.

And still, it’s the little things that trip her up, like a seemingly harmless packet of juice, or a misleading claim on a box of cereal. “I don’t want a label to be a luxury,” she says. “It should be basic. Just tell me what’s in the food. Give me a chance to protect my boys.”

“We are not just advocating for labels, we’re advocating for equity,” says Swakei of NCD Alliance Kenya. “Every child, regardless of where they live or how much their parents know, deserves protection from harmful food marketing and misinformation.”

FOPL could reduce emergency visits. It could prevent severe sugar crashes. It could save money. And most importantly, it could give back a sense of control in a life that so often feels dictated by forces beyond their reach.

According to Beatrice Okere, a clinical dietician, introducing mandatory Front-of-Pack Labelling (FOPL) presents a transformative opportunity for food manufacturers in Kenya. Beyond aligning with global best practices, it allows producers to display clear warning labels on products that are high in nutrients of concern, enhancing consumer trust and brand credibility. “FOPL can empower parents to make informed decisions,” says Beatrice Okere, a clinical dietician.

For food manufacturers, the shift also brings economic incentives. Reformulating products to reduce harmful ingredients not only fosters a competitive edge but may also attract a growing base of health-conscious consumers.

Okere urges parents to be extra vigilant, especially on products with health claims. “Just because a snack claims to be healthy doesn’t mean it’s suitable for your child,” she emphasizes.

When implemented effectively, FOPL could be a game-changer, promoting public health, supporting local businesses, and protecting vulnerable children from long-term complications linked to diet-related diseases.

“We’re not different,” Brian says. “We just know more about our bodies. And we’ve got each other.”

©Citizen Digital, Kenya

Continue reading...

From the outside, 12-year-old Jefferson and his 11-year-old brother Brian (not their real names) look like any other pair of rural Kenyan kids; competitive, playful, brimming with energy.

But beneath their joy lies a carefully measured routine: insulin shots, blood sugar checks, strict meal schedules, and constant vigilance. Because both brothers live with Type 1 diabetes.

Brian, the secondborn, was just four years old when he was diagnosed. His mother, Rose (a pseudonym), had already seen the signs before. Because two years earlier, she had walked the same terrifying path with Jefferson, the eldest. “My parents had encountered it before,” Brian says matter-of-factly. “Through my elder brother, Jefferson. He was diagnosed when he was just two.”

Now in their pre-teen years, both boys have grown up knowing the language of illness. They understand carbs, ketones and how easy it is for one wrong snack to throw their whole body out of balance.

“How Much Sugar Is In This?”

That’s the question that echoes through their household every time a packaged snack enters their orbit, from a roadside mandazi to a brightly-colored packet of biscuits. And it’s not always easy to get an answer.

“Sometimes it says ‘natural flavor’ or ‘no added sugar’, but when I check their blood sugar after, it’s high,” says their mother, Rose, holding up a crumpled snack wrapper. “What do those words even mean? Why can’t it just be clear?”

In her hands is what looks like an ordinary packet,but for her family, it could mean a dangerous sugar spike, a sleepless night, or even a trip to the hospital.

This is why Front-of-Pack Labelling (FOPL) could be a game-changer. FOPL involves placing clear, visible warnings, such as traffic light symbols or black stop signs, on the front of food packages to indicate if a product is high in sugar, salt, or unhealthy fats.

Unlike the confusing jargon of ingredient lists, FOPL speaks plainly. And for families like Rose’s, plain is powerful.

In countries like Chile and Mexico, FOPL has already changed lives. For Chile, according to the Global Food Research Program, Chile’s food labeling law, implemented in phases from 2016 to 2019, requires front-of-package black octagonal warning labels on products high in calories, sugar, saturated fat, or sodium.

These "high in" products cannot carry health claims related to the excess nutrient and face strict marketing restrictions, including bans on child-targeted advertising and limitations on TV ads from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. Additionally, such products cannot be sold or promoted in schools or nurseries.

Mexico has also introduced strict food labeling regulations to promote healthier consumer choices. Under the revised Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-051, implemented in October 2020, packaged foods high in sugars, fats, calories, or sodium must carry black octagonal front-of-pack (FOP) warning labels like “Exceso Azúcares” meaning excess sugars or “Exceso Sodio” meaning “Excess sodium.”

The rollout follows a phased approach: the first phase introduced the warning labels, while the upcoming second phase tightens rules on marketing, restricting the use of characters, endorsements, and health claims on products with warning seals. The aim is to improve transparency and protect public health, especially among children.

But in Kenya, the policy is still in limbo, tangled in red tape, industry resistance, and legislative delay. “We are advocating for the urgent implementation of a front-of-pack warning label system by 2026,” says Anne Swakei, NCD Alliance Kenya, a consortium pushing for action on food environment policies in Kenya. “It’s not just about consumer rights, it’s a public health imperative.”

A Biscuit, a Spike, a Lesson

“One time I ate a biscuit from a shop,” Jefferson recalls. “It looked healthy, brown color, said something about oats. But later, I felt dizzy. I checked my sugar, it was too high.” He shrugs, but the lesson lingers. Not all food that looks healthy is healthy. And not all food that claims to be “natural” is safe for them.

These aren’t lessons a child should have to learn the hard way. But in the absence of effective policy, the burden of education, monitoring, and prevention has fallen almost entirely on Rose’s shoulders.

“We want to help families distinguish between safe and unsafe products instantly,” explains Swakei. “A nutrient profile model (NPM) would classify foods based on saturated fat, sugar, and sodium content and FOPL would bring that information directly to consumers.”

Rose never imagined she’d become an expert in pediatric diabetes. She had never heard of Type 1 until Jefferson collapsed one Sunday morning while getting ready for church.

“I went to dress him. When I lifted him out of bed, he was limp. His mouth was full of thick saliva, and his breath smelled awful. I called his father. He rushed him to hospital.”

She pauses, “I honestly thought they’d be back in time for church.” Instead, she was thrown into a world of IV drips, insulin regimens, blood sugar monitors, and endless questions. “I asked, ‘Diabetes? In a child?’ I thought only old people got it.”

Back home, the questions were crueler. Was it witchcraft? A punishment from God? Why inject a baby? “Some said, ‘Don’t inject him, just pray and it will go.’ Others blamed me. I cried so much. I was green. I didn’t even know how to inject him without hurting him.”

Two years later, Brian fell ill—and Rose’s worst fear returned. Another diagnosis. Another child. Another lifelong journey. “I had become a full-time caregiver, whether I liked it or not.”

A Quiet Father, a Heavy Load

Rose isn’t entirely alone. The boys’ father, once married to another woman, now living apart, does provide financially. He pays school fees, covers some medical costs. But emotionally, and physically, he’s absent. “He’s not really there with us,” Rose admits. “He helps, yes, but the day-to-day, the hospital visits, the insulin checks, that’s all me.”

Rose says that he went back to his first wife, leaving her with the boys. She worries sometimes about what the emotional distance means for her sons. They rarely speak about their father, but she sees it in the quiet moments, when they sit too long by themselves, or when they ask questions she doesn’t always have answers for. “I know they feel the gap. But I also know I have to be strong. For both of them.”

Labels That Could Save a Life

For Rose, every school term is a dance of logistics. Ensuring teachers know the boys’ symptoms. Checking in with the school nurse. Packing snacks. Monitoring moods.

And still, it’s the little things that trip her up, like a seemingly harmless packet of juice, or a misleading claim on a box of cereal. “I don’t want a label to be a luxury,” she says. “It should be basic. Just tell me what’s in the food. Give me a chance to protect my boys.”

“We are not just advocating for labels, we’re advocating for equity,” says Swakei of NCD Alliance Kenya. “Every child, regardless of where they live or how much their parents know, deserves protection from harmful food marketing and misinformation.”

FOPL could reduce emergency visits. It could prevent severe sugar crashes. It could save money. And most importantly, it could give back a sense of control in a life that so often feels dictated by forces beyond their reach.

According to Beatrice Okere, a clinical dietician, introducing mandatory Front-of-Pack Labelling (FOPL) presents a transformative opportunity for food manufacturers in Kenya. Beyond aligning with global best practices, it allows producers to display clear warning labels on products that are high in nutrients of concern, enhancing consumer trust and brand credibility. “FOPL can empower parents to make informed decisions,” says Beatrice Okere, a clinical dietician.

For food manufacturers, the shift also brings economic incentives. Reformulating products to reduce harmful ingredients not only fosters a competitive edge but may also attract a growing base of health-conscious consumers.

Okere urges parents to be extra vigilant, especially on products with health claims. “Just because a snack claims to be healthy doesn’t mean it’s suitable for your child,” she emphasizes.

When implemented effectively, FOPL could be a game-changer, promoting public health, supporting local businesses, and protecting vulnerable children from long-term complications linked to diet-related diseases.

“We’re not different,” Brian says. “We just know more about our bodies. And we’ve got each other.”

©Citizen Digital, Kenya

Continue reading...